The following is one in a regular series of columns that examines and critiques commercial design, as well as provides commentary on current issues and trends in the design industry.

About a year ago, the writers of this column, in an article entitled Breaking the Great Code, mused upon the way in which designers were beginning to look to the street for inspiration.

Overdrawn at the bank of art and design history, and bored with borrowing from each other, they began to appropriate the forms and styles of what we in the trade like to call the ‘vernacular.’

After decades of tireless effort to lift and separate design from the corpus of mainstream commercial art, some designers were now slipping their hands right back for ideas into the deep, dark crevices of the undesigned.

At first, only rogues and iconoclasts were bold enough to take the plunge. Fringe magazines picked up the scent and ran articles about them.

But, before too long, the fruits of these nocturnal adventures began to see the light of day in the more respectable design publications. The judgment was in: we have gone through Jane Doe’s underwear drawer and John Q. Public’s trousers, and they have not even noticed. Hell, we are even winning awards with what we found. Aren’t we clever?

Well, while we were busy giggling at sansabelts and doubleknits, Ms Doe and Mr. Public were going through our laundry, too. And what they found there is cause for alarm.

Suddenly, the closely guarded codes and conventions of basic typographic design are now embedded in even the most rudimentary desktop publishing packages, and Jane and John are using them to produce everything from garage sale signs to birthday party invitations.

Why use markers and photocopiers when you can buy type on a stick?

In horror, one imagines supermarket chatter studded with the arcane terminology once shared by designers and typographers alone:

‘Have you seen the way she kerns her hair?’

‘Yes. And if you ask me, she’s using too much drop shadow.’

In revulsion, one winces at the thought of long-cherished trade secrets being edited down and bundled up for over the counter sales in packages with names such as ‘Disc o’ Fonts,’ ‘Type ‘n’ Stripe,’ or ‘Design Your World.’

The back pages of household publications will offer mail-order courses with titles such as ‘Spec Type in Your Spare Time,’ or, ‘Design Like a Pro in Less Than Ten Minutes.’

The annoying phenomenon of the company president seeking his wife’s approval on the color of his annual report will become the norm. Only it will not just be the color she comments on:

‘Harold, this layout is disgusting. I not only had to change the color to Pantone 376 (avocado green), but I had to switch the font to Doilly Grotesque, and use a whole new set of rags to clean up the line endings. That designer of yours needs a good licking!’

Are you beginning to feel the depth of our terror, the breadth of our panic? Is the gravity of this assault upon the bastions of professional design becoming absolutely clear?

Some of us are only now fully aware of this pernicious threat, and at our wits’ end as to how to deal with it. Bad enough we have to compete with each other. Now we have to worry about the lady next door.

But other, more prescient members of the design profession have seen this coming for some time now. In anticipation of the onslaught, they have girded their keyboards with ever more arcane weaponry.

So you thought typesetting and page layout were easy? You thought you had broken the Great Code? Well, wait till you see design’s newest secret weapon: freeform typography.

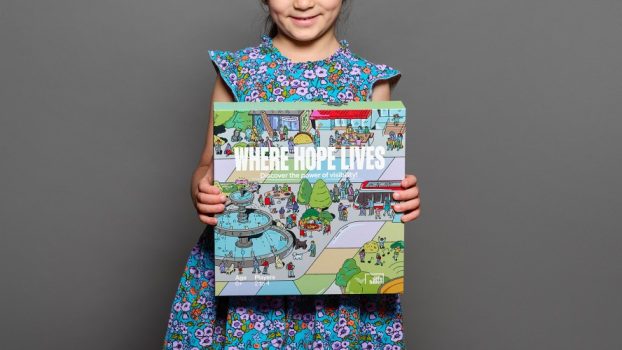

Take a look at the typesetting in the illustrated example below and you will see what freeform really means.

Designed by Pierre di Sciullo (a designer of the French intellectual variety – a sort of Jean-Paul Sartre of the mousepad), this font takes typographic form well beyond the threshold of recognition.

It makes reading all that three-point legal copy on the back of pharmaceutical packs look like a walk in the park.

Yes, this is how we get our revenge. Just try to break the code now.

Will Novosedlik and Bob Russell are principals of Russell Design in Toronto.