As Canadian brands tap into national pride amid trade tensions, do flag-waving ads risk crossing into anti-American sentiment? This story was originally published in the Summer 2025 issue of strategy magazine.

By Will Novosedlik

About a week before the Canadian federal election this past spring, CNN ran a segment featuring host Laura Coates and guest Kevin O’Leary. Coates asked O’Leary if he thought Trump’s tariffs and his insistence on calling Canada the “51st State” would hurt America’s brand. O’Leary brushed the question aside as if such a thing were unimaginable.

However, some data paints a different picture. In mid-March, research firm Morning Consult released findings stating that since Trump took office in January, the average net favourability of the U.S. has fallen by roughly 20 points worldwide, with purchase consideration in Canada, Europe and Asia seeing some of the biggest declines. And according to a mid-February Leger poll, 27% of Canadians consider America as an “enemy country.” Meanwhile, a majority of Americans (56%) consider Canada an “ally.”

Johanna Faigelman, anthropologist and CEO of Human Branding, reminds us that historically Canadians have had an inferiority complex vis-a-vis Americans. “We’re like America’s nicer, more polite, less nationalistic and less individualistic little brother. But that narrative has shifted. Now our big brother wants to beat us up. So we don’t look up to him like we used to. And that has really messed with us. First we were shocked, then we freaked out and then just got really, really angry. And that’s not the narrative we have always told ourselves about ourselves.”

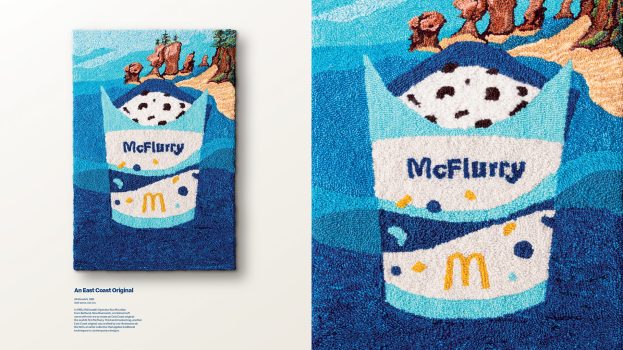

This friction has been showing up in consumer behaviour. The same Leger poll showed that two-thirds of Canadians had reduced their purchases of American products, both in stores (66%) and online (67%); just over half (54%) had decreased purchases from QSRs, like McDonald’s and Starbucks; and 73% said they had increased their purchases of Canadian-made goods.

As a result, we’re seeing homegrown brands respond to this rise in national pride with a spate of ads donning the Canadian maple leaf. But the response is also raising questions among some advertisers: Is the industry reflecting public sentiment, or is it crossing the line between patriotism and antagonism?

A recent Cheesestrings campaign offers an interesting example. Its provocative headline, “Made with 0% American cheese,” risks defining Canadian identity by what it isn’t, says Ron Tite, chief strategy and innovation officer at agency Church+State. “I think things like that have the potential to damage Brand Canada. Saying that we aren’t American is not the same as saying we’re proudly Canadian. Better to believe in ourselves and keep our integrity intact.”

Sabrina Babooram, head of strategy at agency Academy agrees: “I think being anti-American is going to get tiring very quickly. There’s far more potential for our own brands to find the right tonality and build community across Canada.”

“0% American” came from reading the room,” says Marty Hoefkes, CD at Broken Heart Love Affair, the agency behind the Cheestrings work. “When everyone’s reaction to the idea of being America’s 51st state was ‘not a snowball’s chance in hell,’ we felt that being a 100% Canadian cheese brand gave us the license to put those odds in a headline. We knew there was a chance of some backlash and even had a PR team assembled to counter it, but it wasn’t necessary. The response was entirely in our corner, even from all the Americans who talked about it.”

Phillip Haid, CEO of social impact agency Public, concurs with Hoefkes in that “companies are tapping into the sentiment that Canadians are feeling in a very real way. Brands either reflect culture or shape it, and right now these patriotic campaigns are reflecting it. And I think they are reflecting it appropriately…

“[However,] there is a role for Canadian brands to ask what it really means to be Canadian. And how can we reflect that in our advertising by engaging our audiences in provocative ways?”

Take Maple Leaf Foods’ “Look for the Leaf” campaign. The company highlights 15 Canadian brands, other than their own – including Clearly Canadian, Chapman’s Ice Cream, Gay Lea, Dare Foods, Schneiders, High Liner, and others – and encourages Canadians to “Shop the leaf, even if it isn’t ours… because Canadians buying Canadian benefits us all.” It doesn’t get more authentically Canadian than that. The campaign reflects an intuitive truth that, as a culture, we tend to be more focused on the collective good than on individualism.

“This is a huge opportunity for brands that are authentically Canadian to stand up and say, ‘Don’t forget who we are. And who we are as Canadians is not, ‘I hate the enemy,’” adds Babaroom, who was dismayed to see some coffee houses had swapped out “Americano” with “Canadiano” on their menu, which came across as slightly hostile. “At the same time it does not have to be bland and ‘kumbaya.’ It can have some teeth. But the difference is that it’s about us, not about us vs. them.”

Perhaps the best example of this is the recent remake of Molson’s iconic “I Am Canadian” rant from 25 years ago. While the original poked fun at how Americans misunderstand us, it also playfully mocked Canadians while boasting about what makes us great. The remake brings it up to date by adding references to the 51st State while continuing to gently rib at Canada (“the birthplace of universal medical healthcare and the bench-clearing brawl” and “the birthplace of peanut butter, ketchup chips and yoga pants!” for example). It doesn’t finish with “I am Canadian,” but rather with “We are Canadian.”

There’s no question Canadians are frustrated, but will the flare-up become fervour? Or will the “anti-American” sentiment tire out?

Hoefkes believes that all movements tend to die out once “everyone jumps on board” and that “part of our job is paying attention to how people are feeling and meeting them where they are, not fighting to pull them to where we want them. And as long as you’re genuine and have some reason to join the conversation, there’s room for brands to reflect all the emotions that people feel – not just the warm, fuzzy, happy ones.”

That said, “just like it says on Quebec license plates – Je Me Souviens – we will remember,” adds Tite. “I think there will still be a pro-Canadian attitude long after the tariffs go away.”

Part 2 of this feature, Neuroscience meets nationalism, will be published in our daily newsletter on Tuesday.